An Overview of Weak Supervision

Alex Ratner, Stephen Bach, Paroma Varma, Chris Ré

Jul 16, 2017

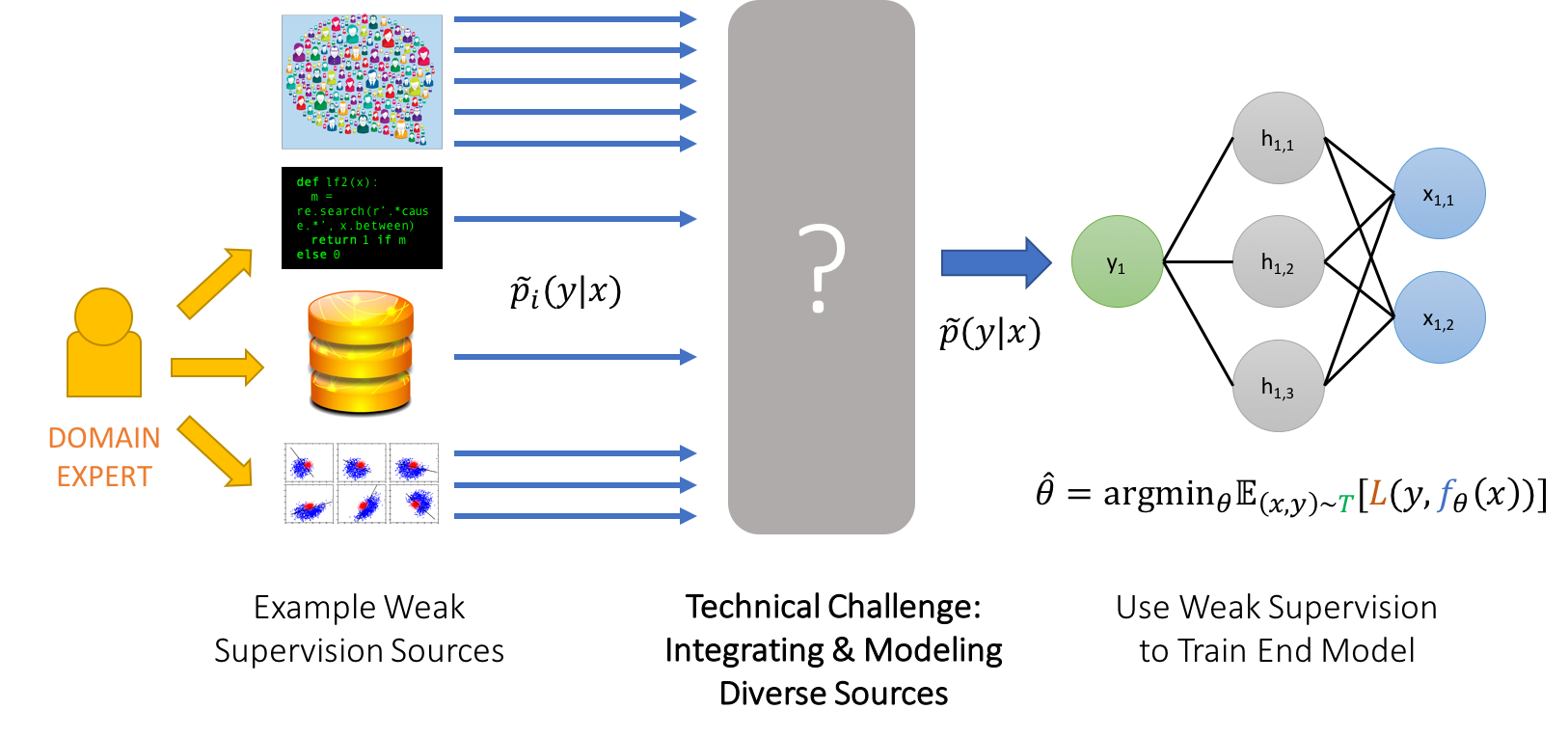

Getting labeled training data has become the key development bottleneck in supervised machine learning. We provide a broad, high-level overview of recent weak supervision approaches, where noisier or higher-level supervision is used as a more expedient and flexible way to get supervision signal, in particular from subject matter experts (SMEs). We provide a simple, broad definition of weak supervision as being comprised of one or more noisy conditional distributions over unlabeled data, and focus on the key technical challenge of unifying and modeling these sources.

# The Training Data Bottleneck

In recent years, the real-world impact of machine learning has grown in leaps and bounds. In large part, this is due to the advent of deep learning models, which allow practitioners to get state-of-the-art scores on benchmark datasets without any hand-engineered features. Whereas building an image classification model five years ago might have required advanced knowledge of tools like Sobel operators and Fourier analysis to craft an adequate set of features for a model, now deep learning models learn such representations automatically. Moreover, given the availability of multiple professional-quality open-source machine learning frameworks like TensorFlow and PyTorch, and an abundance of available state-of-the-art models (with fancy anthropomorphic names to boot), it can be argued that high-quality machine learning models are almost a commoditized resource now. The dream of democratizing ML has never seemed closer!

There is a hidden catch, however: the reliance of these models on massive sets of hand-labeled training data. This dependence of machine learning on labeled training sets is nothing new, and arguably has been the primary driver of new advances for many years (spacemachine.net 2016). But deep learning models are massively more complex than most traditional models–many standard deep learning models today have hundreds of millions of free parameters–and thus require commensurately more labeled training data. These hand-labeled training sets are expensive and time-consuming to create–taking months or years for large benchmark sets, or when domain expertise is required–and cannot be practically repurposed for new objectives. In practice, the cost and inflexibility of hand-labeling such training sets is the key bottleneck to actually deploying machine learning.

That’s why in practice today, most large ML systems actually use some form of weak supervision: noisier, lower-quality, but larger-scale training sets constructed via strategies such as using cheaper annotators, programmatic scripts, or more creative and high-level input from domain experts, to name a few common techniques. The goal of this blog post is to provide a simple, unified view of these techniques along with a summary of some core technical challenges and opportunities in this new regime. We’ll proceed in three main parts:

- We’ll review some other areas of machine learning research similarly motivated by the problem of labeled training data;

- We’ll provide a simple, working definition of weak supervision;

- We’ll discuss the key technical challenge of integrating and modeling diverse sets of weak supervision signals.

# Our AI is Hungry: Now What?

Many traditional lines of research in machine learning are similarly motivated by the insatiable appetite of modern machine learning models for labeled training data. We start by drawing the core distinction between these other approaches and weak supervision at a high-level: weak supervision is about leveraging higher-level and/or noisier input from subject matter experts (SMEs).

For simplicity, we can start by considering the categorical classification setting: we have data points \(x \in X\) that each have some label \(y \in Y = {1,...,K}\), and we wish to learn a classifier \(h : X \rightarrow Y\). For example, \(X\) might be mammogram images, and \(Y\) a tumor grade classification. We choose a model class \(h_\theta\)–for example a CNN–and then pose our learning problem as one of parameter estimation, with our goal being to minimize the expected loss, e.g. on a new unseen test set of labeled data points \((x_i, y_i)\). In the standard supervised learning setting, we then would get a training set of data points with ground-truth labels \(T = {(x_1, y_1), ..., (x_N, y_N)}\)–traditionally, hand-labeled by SME annotators, e.g. radiologists in our example–define a loss function \(L(h(x), y)\), and minimize the aggregate loss on the training set using an optimization procedure like SGD.

The problem is that this is expensive: for example, unlike grad students, radiologists don’t generally accept payment in burritos and free T-shirts! Thus, many well-studied lines of work in machine learning are motivated by the bottleneck of getting labeled training data:

- In active learning, the goal is to make use of subject matter experts more efficiently by having them label data points which are estimated to be most valuable to the model. Traditionally, applied to the standard supervised learning setting, this means selecting new data points to be labeled–for example, we might select mammograms that lie close to the current model decision boundary, and ask radiologists to label only these. However, we could also just ask for weaker supervision pertinent to these data points, in which case active learning is perfectly complementary with weak supervision; as one example of this, see (Druck, Settles, and McCallum 2009).

- In the semi-supervised learning setting, we have a small labeled training set and a much larger unlabeled data set. At a high level, we then use assumptions about smoothness, low dimensional structure, or distance metrics to leverage the unlabeled data (either as part of a generative model, as a regularizer for a discriminative model, or to learn a compact data representation); for a good survey see (Chapelle, Scholkopf, and Zien 2009). More recent methods use adversarial generative (Salimans et al. 2016), heuristic transformation models (Laine and Aila 2016), and other generative approaches to effectively help regularize decision boundaries. Broadly, rather than soliciting more input from subject matter experts, the idea in semi-supervised learning is to leverage domain- and task-agnostic assumptions to exploit the unlabeled data that is often cheaply available in large quantities.

- In the standard transfer learning setting, our goal is to take one or more models already trained on a different dataset and apply them to our dataset and task; for a good overview see (Pan and Yang 2010). For example, we might have a large training set for tumors in another part of the body, and classifiers trained on this set, and wish to apply these somehow to our mammography task. A common transfer learning approach in the deep learning community today is to “pre-train” a model on one large dataset, and then “fine-tune” it on the task of interest. Another related line of work is multi-task learning, where several tasks are learned jointly (Caruna 1993; Augenstein, Vlachos, and Maynard 2015). Some transfer learning approaches take one or more pre-trained models (potentially with some heuristic conditioning of when they are each applied) and use these to train a new model for the task of interest; in this case, we can actually consider transfer learning as a type of weak supervision.

The above paradigms potentially allow us to avoid asking our SME collaborators for additional training labels. But what if–either in addition, or instead–we could ask them for various types of higher-level, or otherwise less precise, forms of supervision, which would be faster and easier to provide? For example, what if our radiologists could spend an afternoon specifying a set of heuristics or other resources, that–if handled properly–could effectively replace thousands of training labels? This is the key practical motivation for weak supervision approaches, which we describe next.

# Weak Supervision: A Simple Definition

In the weak supervision setting, our objective is the same as in the supervised setting, however instead of a ground-truth labeled training set we have:

- Unlabeled data \(X_u = x_1, …, x_N\);

- One or more weak supervision sources \(\tilde{p}_i(y \vert x), i=1:M\) provided by a human subject matter expert (SME), such that each one has:

- A coverage set \(C_i\), which is the set of points \(x\) over which it is defined

- An accuracy, defined as the expected probability of the true label \(y^*\) over its coverage set, which we assume is \(\lt 1.0\)

In general, we are motivated by the setting where these weak label distributions serve as a way for human supervision to be provided more cheaply and efficiently: either by providing higher-level, less precise supervision (e.g. heuristic rules, expected label distributions), cheaper, lower-quality supervision (e.g. crowdsourcing), or taking opportunistic advantage of existing resources (e.g. knowledge bases, pre-trained models). These weak label distributions could thus take one of many well-explored forms:

- Weak Labels: The weak label distributions could be deterministic functions–in other words, we might just have a set of noisy labels for each data point in \(C_i\). These could come from crowd workers, be the output of heuristic rules \(f_i(x)\), or the result of distant supervision (Mintz et al. 2009), where an external knowledge base is heuristically mapped onto \(X_u\). These could also be the output of other classifiers which only yield MAP estimates, or which are combined with heuristic rules to output discrete labels.

- Constraints: We can also consider constraints represented as weak label distributions. Though straying outside of the simple categorical setting we are considering here, the structured prediction setting leads to a wide range of very interesting constraint types, such as physics-based constraints on output trajectories (Stewart and Ermon 2017) or output constraints on execution of logical forms (Clarke et al. 2010; Guu et al. 2017), which encode various forms of domain expertise and/or cheaper supervision from e.g. lay annotators.

- Distributions: We might also have direct access to a probability distribution. For example, we could have the posterior distributions of one or more weak (i.e. low accuracy/coverage) or biased classifiers, such as classifiers trained on different data distributions as in the transfer learning setting. We could also have one or more user-provided label or feature expectations or measurements (Mann and McCallum 2010; Liang, Jordan, and Klein 2009), i.e. an expected distribution \(p_i(y)\) or \(p_i(y\vert f(x))\) (where \(f(x)\) is some feature of \(x\)) provided by a domain expert as in e.g. (Druck, Settles, and McCallum 2009).

- Invariances: Finally, given a small set of labeled data, we can express functional invariances as weak label distributions–e.g., extend the coverage of the labeled distribution to all transformations of \(t(x)\) or \(x\), and set \(p_i(y\vert t(x)) = p_i(y\vert x)\). In this way we view techniques such as data augmentation as a form of weak supervision as well.

Given a potentially heterogenous set of such weak supervision sources, we can conceptually break the technical challenges of weak supervision into two components. First, we need to deal with the fact that our weak sources are noisy and conflicting–we view this as the core lurking technical challenge of weak supervision, and discuss it more further on. Second, we need to then modify the traditional empirical risk minimization (ERM) framework to accept our weak supervision.

In some approaches, such as in our data programming work (A. J. Ratner et al. 2016), we explicitly approach these as two separate steps, first unifying and modeling our weak supervision sources as a single model \(p(y\vert x)\), in which case we can then simply minimize the expected loss with respect to this distribution (i.e. the cross-entropy). However, many other approaches either do not deal with the problem of integrating multiple weak supervision sources, or do so jointly with training an end model, and thus primarily highlight the latter component. For example, researchers have considered expectation criteria (Mann and McCallum 2010), learning with constraints (Becker and Hinton 1992; Stewart and Ermon 2017), building task-specific noise models (Mnih and Hinton 2012), and learning noise models simultaneously during training (Xiao et al. 2015).

# Wait, But Why Weak Supervision Again?

At this point, it’s useful to revisit and explicitly frame why we might want to use the outlined approach of weak supervision at all. Though heretical-sounding, non-ML approaches are adequate for many simple tasks, as are simple models trained on small hand-labeled training sets! Roughly, there are three principal reasons to motivate a weak supervision approach:

- If we are approaching a challenging task that requires a complex model (i.e. one that has a large number of parameters) then we generally need a training set too large to conveniently label by hand. Most state-of-the-art models for tasks like natural language and image processing today are massively complex (e.g. \(\vert \theta\vert = 100M+\)), and thus are a good fit for weak supervision!

- In some simple cases, the weak supervision sources described above (or a unified model of them, as we’ll discuss in the next section) might be a good enough classifier on their own. However, in most cases we want to generalize beyond the coverage of our weak supervision sources. For example, we might have a set of precise but overly narrow rules, or pre-trained classifiers defined over features not always available at test time (such as models trained over text radiology reports, when our goal is to train an image classifier)–thus we aim to train an end model that can learn a more general representation.

- While other areas of work are also motivated by the bottleneck of labeled training data as discussed, if we have domain expertise to leverage, then weak supervision provides a simple, model-agnostic way to integrate it into our model. In particular, we are motivated by the idea of soliciting domain expert input in a more compact (and thus perhaps noisier) form; e.g. quickly getting a few dozen rules, or high-level constraints, or distant supervision sources, rather than a few million single-bit labels from subject matter experts.

Now that we’ve defined and situated weak supervision, on to the core technical challenges of how to actually model it!

# The Lurking Technical Challenge: Learning a Unified Weak Supervision Model

Given a set of multiple weak supervision sources, the key technical challenge is how to unify and de-noise them, given that they are each noisy, may disagree with each other, may be correlated, and have arbitrary (unknown) accuracies which may depend on the subset of the dataset being labeled. We can phrase this task very generally as that of defining and learning a single weak supervision model, \(\tilde{p}(y\vert x, …)\), defined over the weak supervision sources. We can then think of breaking this down into three standard modeling tasks:

- Learning accuracies: Given some model structure, and no labeled data, how can we learn the weights of this model (which in the basic independent case would represent the accuracies of each weak supervision source)?

- Modeling correlations: What structure should we model between the weak supervision sources?

- Modeling “expertise”: How should we condition the model–e.g. the estimates of how accurate each weak supervision source is–on the data point \(x\)? For example, should we learn that certain weak supervision sources are more accurate on certain subsets of the feature space?

Techniques for learning the accuracies of noisy supervision sources (1) in the absence of ground-truth data have been explored in the crowdsourcing setting, i.e. with a large number of deterministic label sources each having small coverage (Berend and Kontorovich 2014; Zhang et al. 2014; Dalvi et al. 2013; Dawid and Skene 1979; Karger, Oh, and Shah 2011). In the natural language processing community, the technique of distant supervision–heuristically mapping an external knowledge base onto the input data to generate noisy labels–has been used extensively, with various problem-specific modeling solutions to the challenge of resolving and denoising this input (Alfonseca et al. 2012; Takamatsu, Sato, and Nakagawa 2012; B. Roth and Klakow 2013). Our work on Data Programming (A. J. Ratner et al. 2016) builds on these settings, considering the case of deterministic weak supervision sources which we characterize as being produced by black-box labeling functions \(\lambda_i(x)\), where we learn a generative model to resolve and model the output of these labeling functions. Similar approaches have been explored recently (Platanios, Dubey, and Mitchell 2016), as well as in classic settings such as co-training (Blum and Mitchell 1998) and boosting (Schapire and Freund 2012), and in the simplified context of learning from a single source of noisy labels (Bootkrajang and Kabán 2012).

For the same Data Programming setting, we also recently addressed the modeling task (2) of learning correlations and other dependencies between the labeling functions based on data (Bach et al. 2017). Modeling these dependencies is important because, without them, we might misestimate the accuracies of the weak signals and therefore misestimate the true label \(y\). For example, not accounting for the fact that two weak signals are highly correlated could lead to a double counting problem. While structure learning for probabilistic graphical models is well-studied in the fully supervised case (Perkins, Lacker, and Theiler 2003; Tibshirani 1996; Ravikumar et al. 2010; Elidan and Friedman 2005), with generative models for weak supervision the problem is more challenging. The reason is that we have to deal with our uncertainty about the latent class label \(y\).

Finally, the question of modeling expertise or conditioning a weak supervision model can also be viewed as learning local models or a combination of models for a single dataset, such as mixture-of-models and locally-weighted support vector machines. Using local predictors is also relevant in the area of interpretable machine learning as described in (Ribeiro, Singh, and Guestrin 2016). Local predictors that are specialized for different subsets of data have also been studied for time series prediction models (Lau and Wu 2008). In cases where ground truth labels are not available, modeling “expertise” has been studied in the crowdsourcing setting (Ruvolo, Whitehill, and Movellan 2013), where a probabilistic model is used to aggregate crowdsourced labels with the assumption that certain people are better at particular kinds of data and not others. Extending this to the weak supervision setting, our work in (Varma et al. 2016) automatically finds subsets in the data that should be modeled separately by using information from the discriminative model.

# Next Steps Vision: A New Programming Paradigm for Supervising ML

The most exciting opportunity opened up by the perspective of weak supervision, in our opinion, is that by accepting supervision that is weaker–and handling this using the appropriate methods behind the scenes–we can allow users to provide higher-level, more expressive input, and be robust to inevitable lack of precision, coverage, or conflict resolution in this input. In other words, we can define flexible, efficient, and interpretable paradigms for how to interact with, supervise, and essentially “program” machine learning models! On the systems side, we’ve started down this path with Snorkel, where users encode weak supervision sources as deterministic labeling functions; other weakly-supervised frameworks include programming via generalized expectation criteria (Druck, Settles, and McCallum 2009), annotator rationales (Zaidan and Eisner 2008), and many others. We believe the best is yet to come, and are very excited about how weak supervision approaches continue to be translated into more efficient, more flexible, and ultimately more usable systems for ML!

# Weak Supervision Reading Group @ Stanford

Our goal is to grow and expand the above description of weak supervision, and to help with this we’ve started a weak supervision reading group at Stanford. We’ll keep this post updated with what we’re reading, with links to notes when available (coming soon). Please let us know if there are papers we should be reading in the below comments section!

# References

-

Alfonseca, Enrique, Katja Filippova, Jean-Yves Delort, and Guillermo Garrido. 2012. “Pattern Learning for Relation Extraction with a Hierarchical Topic Model.” In Proceedings of the 50th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Short Papers-Volume 2, 54–59. Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Augenstein, Isabelle, Andreas Vlachos, and Diana Maynard. 2015. “Extracting Relations Between Non-Standard Entities Using Distant Supervision and Imitation Learning.” In Proceedings of the 2015 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 747–57. Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Bach, Stephen H, Bryan He, Alexander Ratner, and Christopher Ré. 2017. “Learning the Structure of Generative Models Without Labeled Data.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:1703.00854.

-

Becker, Suzanna, and Geoffrey E Hinton. 1992. “Self-Organizing Neural Network That Discovers Surfaces in Random-Dot Stereograms.” Nature 355 (6356). Nature Publishing Group: 161.

-

Berend, Daniel, and Aryeh Kontorovich. 2014. “Consistency of Weighted Majority Votes.” In NeurIPS 2014.

-

Blum, Avrim, and Tom Mitchell. 1998. “Combining Labeled and Unlabeled Data with Co-Training.” In Proceedings of the Eleventh Annual Conference on Computational Learning Theory, 92–100. ACM.

-

Bootkrajang, Jakramate, and Ata Kabán. 2012. “Label-Noise Robust Logistic Regression and Its Applications.” In Joint European Conference on Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases, 143–58. Springer.

-

Caruna, R. 1993. “Multitask Learning: A Knowledge-Based Source of Inductive Bias.” In Machine Learning: Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference, 41–48.

-

Chapelle, Olivier, Bernhard Scholkopf, and Alexander Zien. 2009. “Semi-Supervised Learning (Chapelle, O. et Al., Eds.; 2006)[book Reviews].” IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks 20 (3). IEEE: 542–42.

-

Clarke, James, Dan Goldwasser, Ming-Wei Chang, and Dan Roth. 2010. “Driving Semantic Parsing from the World’s Response.” In Proceedings of the Fourteenth Conference on Computational Natural Language Learning, 18–27. Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Dalvi, Nilesh, Anirban Dasgupta, Ravi Kumar, and Vibhor Rastogi. 2013. “Aggregating Crowdsourced Binary Ratings.” In Proceedings of the 22Nd International Conference on World Wide Web, 285–94. WWW ’13. doi:10.1145/2488388.2488414.

-

Dawid, Alexander Philip, and Allan M Skene. 1979. “Maximum Likelihood Estimation of Observer Error-Rates Using the Em Algorithm.” Applied Statistics. JSTOR, 20–28.

-

Druck, Gregory, Burr Settles, and Andrew McCallum. 2009. “Active Learning by Labeling Features.” In Proceedings of the 2009 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing: Volume 1-Volume 1, 81–90. Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Elidan, Gal, and Nir Friedman. 2005. “Learning Hidden Variable Networks: The Information Bottleneck Approach.” Journal of Machine Learning Research 6 (Jan): 81–127.

-

Guu, Kelvin, Panupong Pasupat, Evan Zheran Liu, and Percy Liang. 2017. “From Language to Programs: Bridging Reinforcement Learning and Maximum Marginal Likelihood.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:1704.07926.

-

Karger, David R, Sewoong Oh, and Devavrat Shah. 2011. “Iterative Learning for Reliable Crowdsourcing Systems.” In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 1953–61.

-

Laine, Samuli, and Timo Aila. 2016. “Temporal Ensembling for Semi-Supervised Learning.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:1610.02242.

-

Lau, KW, and QH Wu. 2008. “Local Prediction of Non-Linear Time Series Using Support Vector Regression.” Pattern Recognition 41 (5). Elsevier: 1539–47.

-

Liang, Percy, Michael I Jordan, and Dan Klein. 2009. “Learning from Measurements in Exponential Families.” In Proceedings of the 26th Annual International Conference on Machine Learning, 641–48. ACM.

-

Mann, Gideon S, and Andrew McCallum. 2010. “Generalized Expectation Criteria for Semi-Supervised Learning with Weakly Labeled Data.” Journal of Machine Learning Research 11 (Feb): 955–84.

-

Mintz, Mike, Steven Bills, Rion Snow, and Dan Jurafsky. 2009. “Distant Supervision for Relation Extraction Without Labeled Data.” In Proceedings of the Joint Conference of the 47th Annual Meeting of the Acl. http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1690219.1690287.

-

Mnih, Volodymyr, and Geoffrey E Hinton. 2012. “Learning to Label Aerial Images from Noisy Data.” In Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Machine Learning (Icml-12), 567–74.

-

Pan, Sinno Jialin, and Qiang Yang. 2010. “A Survey on Transfer Learning.” IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 22 (10). IEEE: 1345–59.

-

Perkins, Simon, Kevin Lacker, and James Theiler. 2003. “Grafting: Fast, Incremental Feature Selection by Gradient Descent in Function Space.” Journal of Machine Learning Research 3 (Mar): 1333–56.

-

Platanios, Emmanouil Antonios, Avinava Dubey, and Tom Mitchell. 2016. “Estimating Accuracy from Unlabeled Data: A Bayesian Approach.” In International Conference on Machine Learning, 1416–25.

-

Ratner, Alexander J, Christopher M De Sa, Sen Wu, Daniel Selsam, and Christopher Ré. 2016. “Data Programming: Creating Large Training Sets, Quickly.” In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 3567–75.

-

Ravikumar, Pradeep, Martin J Wainwright, John D Lafferty, and others. 2010. “High-Dimensional Ising Model Selection Using ℓ1-Regularized Logistic Regression.” The Annals of Statistics 38 (3). Institute of Mathematical Statistics: 1287–1319.

-

Ribeiro, Marco Tulio, Sameer Singh, and Carlos Guestrin. 2016. “Why Should I Trust You?: Explaining the Predictions of Any Classifier.” In Proceedings of the 22nd Acm Sigkdd International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 1135–44. ACM.

-

Roth, Benjamin, and Dietrich Klakow. 2013. “Combining Generative and Discriminative Model Scores for Distant Supervision.” In EMNLP, 24–29.

-

Ruvolo, Paul, Jacob Whitehill, and Javier R Movellan. 2013. “Exploiting Commonality and Interaction Effects in Crowd Sourcing Tasks Using Latent Factor Models.” In Proc. Neural Inf. Process. Syst., 1–9.

-

Salimans, Tim, Ian Goodfellow, Wojciech Zaremba, Vicki Cheung, Alec Radford, and Xi Chen. 2016. “Improved Techniques for Training Gans.” In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2234–42.

-

Schapire, Robert E, and Yoav Freund. 2012. Boosting: Foundations and Algorithms. MIT press.

-

spacemachine.net. 2016. “Datasets over Algorithms.” http://www.spacemachine.net/views/2016/3/datasets-over-algorithms.

-

Stewart, Russell, and Stefano Ermon. 2017. “Label-Free Supervision of Neural Networks with Physics and Domain Knowledge.” In AAAI, 2576–82.

-

Takamatsu, Shingo, Issei Sato, and Hiroshi Nakagawa. 2012. “Reducing Wrong Labels in Distant Supervision for Relation Extraction.” In Proceedings of the 50th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Long Papers-Volume 1, 721–29. Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Tibshirani, Robert. 1996. “Regression Shrinkage and Selection via the Lasso.” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological). JSTOR, 267–88.

-

Varma, Paroma, Rose Yu, Dan Iter, Christopher De Sa, and Christopher Ré. 2016. “Socratic Learning: Empowering the Generative Model.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:1610.08123.

-

Xiao, Tong, Tian Xia, Yi Yang, Chang Huang, and Xiaogang Wang. 2015. “Learning from Massive Noisy Labeled Data for Image Classification.” In Proceedings of the Ieee Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2691–9.

-

Zaidan, Omar F, and Jason Eisner. 2008. “Modeling Annotators: A Generative Approach to Learning from Annotator Rationales.” In Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 31–40. Association for Computational Linguistics.

-

Zhang, Yuchen, Xi Chen, Denny Zhou, and Michael I Jordan. 2014. “Spectral Methods Meet Em: A Provably Optimal Algorithm for Crowdsourcing.” In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 27, 1260–8. http://papers.neurips.cc/paper/5431-spectral-methods-meet-em-a-provably-optimal-algorithm-for-crowdsourcing.pdf.